Educational 3D design workshop : test of an online metaverse platform « Spatial.io » (partnership between ENSA Nantes, France and Nirma University, India)

This first research report conducted at the CRENAU laboratory is part of the BIMaHEAD research project. It includes the presentation of the SPATIAL.IO metaverse platform, subject to the educational and conceptual experience offered jointly to architecture students from ENSA Nantes and Nirma University.

a. Preliminary preparations for the Workshop

During the week of February 21 to 27, 2022, workshops are organized in partnership with Nirma University, a private Indian school. During this week, the topic is aboutncollecting information during the educational experience carried out on the Spatial.io platform. The experiments under study are conducted at ENSA Nantes, with french students and teachers. The interaction between the two partner groups will question us about the possible cultural differences noted in the handling of the metaverse studied platform. Among the planned experiments, a 1 hour experiment at the Coraulis is planned in order to confront this immersive device with the issues raised by the workshop (quality of immersion in the platform and use for design purposes). On February 17, a meeting is organized with the Indian participants of the Workshop, the objective of the meeting is to prepare the students on the theme of the experience to come. Like the Matryoshka, the Spatial.io experience tests the stratifications in the design of the architectural project. The Russian doll effect is a metaverse metaphor, forming layers of project: it is an architecture project within a metaverse project. The challenge for the students is to create the context that will host the designed architectural project, and to reproduce the stages of the design process. The students will be able to experiment with new ways of project’s presenting – outside the framework of the studio – by choosing a project that is already modeled or creating one for the occasion (by favoring a small-scale project to limit the difficulties in importing, the urban projects can be chosen, taking care however to choose a relevant scale of presentation).

b. WORKSHOP CONDITIONS (organize study groups and prepare conducive conditions to experimentation)

– organising the time for observation

First of all, in order to document the process, photos are taken around the real space and filmed according to a precise multi-task schedule. The latter allows the different researchers and coordinators during the workshop to know what is relevant to film and when (defined by the « events » programmed beforehand, i.e. the different precise experiments planned for each day). The content manipulated by the students is prepared in advance in order to limit the waste of time, the students will be able to start from demos available on the site. A request is also made to the school’s IT department to allow free access to this site, which is automatically blocked on the protected network.

– create two rooms

The creation of two rooms per participant is envisaged: one to document the process as the days go by, the other to work on the content of the daily creations.

Thus, their comparisons would make it possible to measure the possible improvement of the handling according to the various days. It will also be a question of generating a portal between the two rooms in order to connect these two work rooms for the students themselves and for the teachers.

We can ask ourselves: Do teachers and students navigate between these two rooms, do they use the resource from previous days? Do they build on what they have done before or do they recreate a whole new world each day? Are both rooms used, or is one of them predominantly favoured?

– dividing and coordinating groups

The creation of several groups is envisaged in order to carry out the experiment efficiently between the schools. During the workshop, the students will prepare their room and discover how to use the platform’s tools. It will be important to record and document their reactions to the design process, what they handle first, their comfort with the tools, etc.

One difficulty is to connect the groups while ensuring a coherent and fluid future analysis. A proposal was made to define French ambassadors to react and visit the models of the other students, before the intervention of the teachers. A technical question should be asked first to the student before the teacher of the group. However, it is acknowledged that inter-school collaborations will be limited in the real conditions of the experiment, as well as some preconceived prerequisites.

c. OBSERVE DURING THE WORSHOP (collect data from the experiment, and transmit it for analysis)

Several dimensions are to be considered through this virtual reality experience: the face-to-face and remote unfolding via the participants’ respective screens. In this case, an observant person is in charge of filming and documenting the in-person experience using a camera, available for loan from the laboratory.

This task consists in recording the data of the experiment, and transmitting them for analysis in a second step. The video recording is based on the identification of actual physical interactions and behaviours for each day during the specific event planned. This also includes criticisms and feelings, adaptations to the statement, discussions between students, difficulties encountered, gatherings and dispersals of people and tasks, strategies deployed before and during the experiment (are paper sketches or mock-ups observed before or during the design? Are group discussions pivotal? What physical space do the participants occupy, do they display ideas in space…). In parallel, these observations are recorded in a written summary according to a protocol of criteria defined for the fluid use of this type of platform. The time is reported for each observation or remark taking place in the physical world. In this way I develop an observation method with an ethnographic form. The latter corresponds to the observation of the study group of architecture students at ENSA. The method focuses on the interactions, behaviours and strategies of use of the metaverse platform under consideration: Spatial.io. The report contains several estimation points (from 0 to 5) according to the group of students and the day of the experiment considered: frequency of use of the VR headset, frequency of use of the 2D and 3D tools (nature: hand sketch, physical model, software sketch, 3D software model), use of the platform (nature: existing objects, staged presentation space, hybridized with other platforms Slack, Zoom, Google Drive,…), « in process » workspace), investment of the physical space (nature: Displays, studio screen, other computers, other classroom), peer engagement (verbal/visual), peer interactions (nature: technical help (requested or provided), design process, platform critique (positive or negative), distraction), frequency of interactions with teachers, focus on the time of the experience, work strategy (individual/group), formal restitutions presented (nature: browsing within one room, browsing between multiple rooms, digital images, printed images), and activities by time.

Additional remarks are also crucial in order to note other types of behaviour (content of the criticisms formulated, course of the experience,…).

In the framework of the research, a consent contract must also be signed beforehand by the participants, in order to legally document the observed process.

The remote capture is taken care of on Zoom in order to collect the digital process and compare it to the physical interactions (i.e. how are these observations translated into Spatial? what kind of content is published by the students, what lights, what textures are mobilised and within what limits ?)

d. Research in the field of VR applied to education : the example of Spatial

Observations of user behaviour in virtual reality are currently limited, and there are few concrete practical cases. It seems relevant to first turn to digital ethnography, in order to examine the reactions and feedback of people in their virtual experience. The above-mentioned workshop also aims to fill this gap and to collect analysable data for a given platform: Spatial.io.

– SPATIAL.IO: a multi-user metaverse platform

Several themes interest the research in its pedagogical approach, as well as the interweaving of physical and virtual tools during such an experience :

The notion of physical distance exists in the virtual world, between avatars. Certain bugs or defects can create discomfort in the disturbed perception of one’s virtual body (e.g. lack of resistance of the physical manifestation of avatars, « ghost » effect). The feeling of real presence is tangible: it can create discomfort if it is not measured with finesse. It is therefore possible to invade someone’s personal space if and vice versa if this parameter is not properly adjusted. However, these questions of ‘personal space’ or ‘kinesphere’ (Rudolph Laban’s term for the limits of his gesture around his body) raise issues of subjective perception. How can we define a personal sphere that is fair and comfortable for the user if it has to do with a very personal feeling? Moreover, is this discomfort in use the result of a human apprehension of the body world or simply the reflection of cultural differences?

In a digitalized world, touch is very meaningful and refers to a differentiated use according to the context. Depending on the degree of intimacy with other users, the right physical distance can be very different. These are parameters that seem interesting to be able to set at one’s convenience (by considering a maximum distance tolerated by the platform, adjustable; specific modes « between friends », « visitors », « pro »,… as may exist for other communication platforms. Instagram, which is currently an offshoot of MetaFacebook, offers its users a professional, private or public account.) These concerns therefore pursue the virtual world in its professional use and raise the question of the limits that one adopts according to the scope of use envisaged. Is it desirable to imagine « professional » avatars that are nevertheless customisable? Spatial.io proposes, for example, to embed a photo of the face on the owner’s avatar. However, it is common to observe a great deal of freedom in the choice of these avatars (a choice that is not insignificant when we consider the notion of exacerbated physical reflection described above), fuelled by a culture of the absurd, of the incongruous conveyed by a fantasy heritage. What is not possible in the real world becomes an unlimited playground in self-projection: it becomes possible to appear as a non-human, a fictional character, etc….

If metaverses can be extrapolated to alternative versions of the physical world, vigilance is required with regard to potential abuses – the first cases of virtual sexual aggression have been recorded, and the absence of filters or clear legislation on this subject can lead to violence.

Do students use Spatial to design or to walk through the model?

One remark can be made : the fascinating effect of the different universes makes the user want to explore the possibilities of creation before creating by himself. The home interface shows these possibilities through a gallery of creations highlighted by the algorithm. The latter favours the most visited content, which increases the probability of being selected even more regularly.

– Efficiency criteria studied : (questions to be checked as a tester alone /then to be observed during the collective experience of the Workshop)

-Loading of elements into the platform (3D models, images, videos, etc.)

Is the loading fast? Are the compatible formats varied? Is the maximum weight sufficient? Does the import preserve the quality/resolution?

-Creation and customisation of your own world (avatar, scenery, soundscape,…)

How far can you customise your avatar? Can the experience be described as « realistic »? Is the quality of the visual and sound atmosphere satisfactory with or without a VR headset?

-Multi-user management

Does the presence of several people cause lag? Can the different users navigate smoothly? What are the possibilities for interaction between users? Is there any interference in these interactions? What are the predominant interactions that can be observed?

-distance and object management

Does the position of the avatar conform to the real space? Does the minimum and maximum physical distance between users allow for comfortable navigation? Are the objects manipulable?

-Variety of possible media (computer, phone, web version…) / VR and non-VR

Are the web versions usable on computer and phone? What dimension does VR bring to navigation and design?

-Effectiveness of portals

How many portals can be formed at most? Is navigation between portals easy/fast?

– DIFFICULTIES IN USING THE PLATFORM: what are the limits ?

(testing: navigation and design issues)

Today, metaverse platforms are in full expansion, with their share of advantages, criticisms and grey areas. Spatial.io is no exception: numerous updates are made every month to improve the user experience and make it accessible to a larger number of people. We are witnessing a real vulgarisation of virtual spaces and tools attributed to their diffusion and use by a lambda public.

Our view as architects on these current platforms lies in particular in the analysis of their assets for educational purposes. Designing in a collaborative mode, in real time, with a wider panel of individuals (without the need for constant face-to-face interaction) seems to be a complementary way of putting conceptual projects into perspective. What facilitation potential (or even playful potential) for spatial design can thus be found in a new use of these tools? What difficulties – subject to improvement – are encountered during the virtual experience on this type of platform ?

GENERAL EXPERIENCE: NAVIGATING AND CREATING IN SPACE

The first step is to test the Spatial platform, then to examine similar platforms and test their limits. The pedagogical notion is studied and intervenes in the way of apprehending the design process (what is missing, what is difficult to manipulate…). The equipment at my disposal in the laboratory is an Oculus Quest 2 headset, which I configured with the help of the IT team present at CRENAU in order to continue these tests in VR conditions.

During the testing of the Spatial grip, we quickly notice several difficulties. Posting 3D or video content must indeed respect a maximum file size that is quite small compared to the average size of a complete architectural model, or a video of a few minutes. Moreover, the loading time of these elements in a « room » is important (whether it is a video, photo, or model). We can wonder about the potential that such a field of possibilities could offer: a simple 3D design mode could be directly integrated into the platform? The possibilities of sketching exist on Spatial but the modelling of simple forms is not yet developed, which requires working with an additional software. On the other hand, drawing during the presentation is possible but it requires additional skills with the VR headset.

Interactions with objects are limited: the scales of the different elements can be modified, but it is not planned to change their shape or colour. The management of dimensions is also dependent on the scale: the only adjustable parameter is the x, y, z axes (in VR, these parameters are simplified but the grip of the virtual hands is sometimes imprecise). For left-handed people, it is sometimes difficult to manipulate certain tools in VR. Sketching, for example, is by default programmed on the right hand, it is necessary to configure it each time. Eye fatigue also develops very quickly, making the experience difficult to sustain over a long period of time. There are no really easy backtracking possibilities, no « ctrl Z » effect for certain operations. In a make, break and redo approach, this is problematic from a design point of view – it sometimes slows down the creative process when you realise you have made a mistake or want to make a change. If the model is imported into Spatial and needs to be changed in the projected context, the model has to be deleted, modified in another software and then re-imported. This takes extra time and hinders the design without facilitated real-time modification.

On Spatial, an online experience is possible on a computer without the need to download an application. A simple connection to a Google or Facebook account is all that is required to access the content. Compatibility on phones with Android and Apple systems allows access to a larger number of people.

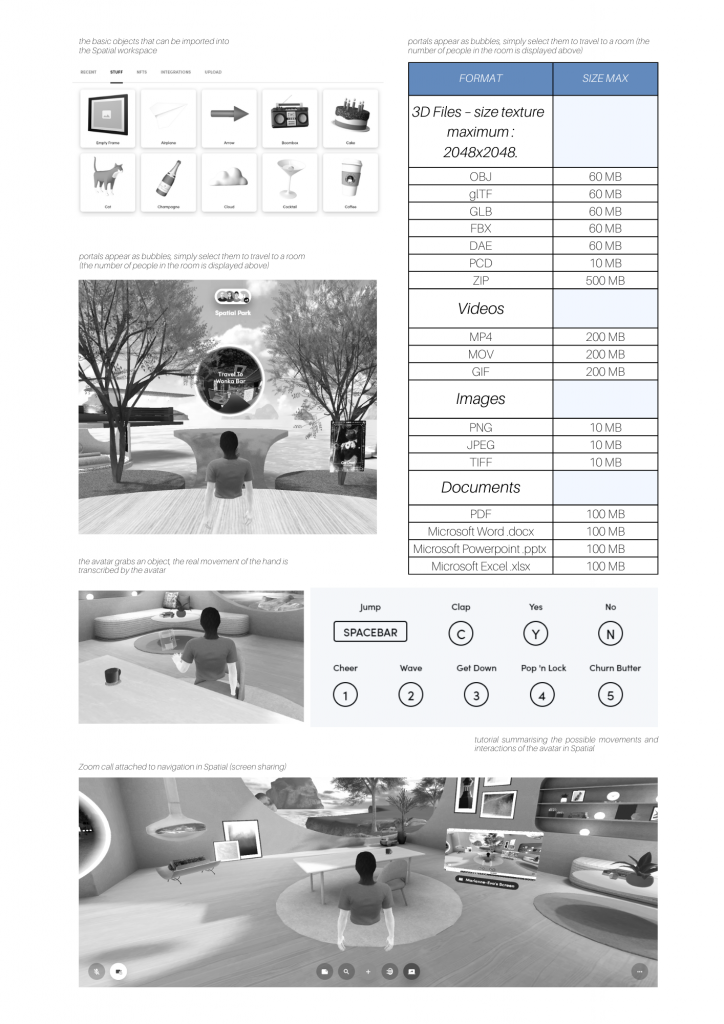

The presence of icons in the interface makes it easy to use the basic objects of the platform.

CUSTOMISE YOUR AVATAR

The design of an avatar is also personalized. To create an avatar, it is possible to use a photo of oneself (realistic avatar on space from a 2D photo) and very simply by taking a photo on one’s smartphone in selfie mode. However, the avatar can be quite far from its physical body when used by several users in the same place (on a phone in particular), which can be disturbing for the participants in terms of the spatialization of its virtual body. The body is also represented by a bust and navigates according to a sliding mouse movement. This may be disturbing at first glance in its perception on the screen, however this system is efficient in VR. It focuses the experience on what is essentially visible: the avatar’s hands, although they are quite disembodied and floating.

The possibilities of movement of the avatar: moving, jumping, dancing, turning, clapping, ducking, etc. allow for multiple interactions with other users and provide a playful framework to the experience.

There is an interaction between the object and the avatar: the avatar moves when the object is grabbed. These details contribute to the immersive character of the experience.

SETTING THE SCENE FOR YOUR WORLD

The existence of easily generated « portals » is an original system for travelling from room to room. This notion of inter-object connections also exists within the same room: it allows links to be made between different elements (e.g. a model linked to a video, a sound, an image / itself linked to a different room by the portal system forming a clickable preview bubble).

Moreover, the scenographic potential is palpable in this type of environment: the staging of its presentation universe can be very rich, as shown by the variety of proposals in the « discovery » gallery. The creation of a wide variety of atmospheres (from a museum atmosphere to a forest atmosphere, for example) helps to qualify the intentions behind the project design. This is a strong pedagogical point because it puts the context of the presentation in relation to the background. The richness of these ambiances follows the increasing progress offered by the platform in creation mode… However, the management of hindsight is limited to the room’s predeterminations. This allows a conforming vision of the set elements, but prevents a good overall vision complementary to the immersive vision. The relationship to the ground is also rather floating: the ground level cannot be re-considered, it remains fixed. If a platform is designed on the ground for example, the object must systematically be repositioned according to a coherent level. There are currently no pre-view cameras that would allow a visualisation of selected points for guest visitors to the room.

In reality, creating your own context in a convincing way is not easy (animations around the stage, management of the horizon, etc.), and it takes some time to master. It is difficult to train oneself to certain points of room customization, external tutorials and expert help from other people are a necessity to be able to appropriate certain features. Considering courses given by real people in real life, on the use of the platform itself, would be a good way to save time on mastering VR tools for the general public. Demos and disembodied tutorials do not always work well to adapt to individual cases and creative ambitions. A VR course in a VR world would be a good way to learn about these tools according to one’s comfort level.

IMPORTING OBJECTS INTO SPATIAL

A bank of objects exists in the platform in addition to the elements that can be imported from outside. It is sometimes easier to set up the scene and objects directly on the computer, then adjust them on the headset to experience the immersion – rather than starting from the design on the headset. If you don’t have a lot of physical space to work with, it’s quite tricky. I have difficulties with character animation for example (imported from outside via MIXAMO and from personal 3D models). The animation is capricious, the character imports correctly but the character is not always animated.

I have the opportunity to test different formats in order to import external 3D models: the .fbx format is to be preferred, because it is easily readable. For downloaded objects and elements, the .obj format may also be suitable. The import time is assured and reduced. The Spatial.io support site recommends the following formats and weights (see following table). In practice, on a school wifi as proposed by ENSA Nantes, the maximum weight tolerated depends on a given import time. The slowness of a connection can lead to the failure of the loading. Therefore, a maximum of 30 to 40 MB is to be preferred in order to guarantee a successful import and a smooth navigation. Indeed, the more the document is loaded with different and heavy elements, the more the fluidity is disturbed. A pdf of 100 MB is also very heavy, during the test such a pdf is difficult to import into the room. These values are to be considered as an indication of the maximum possibilities, they do not guarantee the correct import on the platform (or in a very long time, which is not ideal during the design). The difficulties in importing elements do not make the design obvious, which can generate frustration for the user and break the rhythm of work during the design. The platform is therefore very interesting in terms of its relationship with the context and the consideration of ambiences in several dimensions (sound, visual, etc.), but should be imagined in a fragmented design in several different objects, including when modelling an architectural project.

It is also now possible to import NFTs that the user already owns. This aspect of the metaverse in its economic model and environmental impact is highly questionable. This may raise questions about the coherence of a pedagogical proposal with a platform that is part of a given economic model.

MULTI-USER MANAGEMENT

A maximum of 50 users can be present in the same room. The maximum number of portals is also very important. There are no limits, except for the capacity of the media used. More than 50 portals can be generated without any problems. It is possible to increase this limited number by pairing the platform with a Zoom meeting. With a free Zoom account, up to 100 participants can be broadcast for a maximum of 40 minutes. A window appears and the meeting is broadcast live. Connecting to other platforms such as Slack can be useful, as it is a messaging system that allows real-time chat. Spatial.io can also be affiliated with Google Drive, Figma, MetaTask etc. In Spatial.io on the web, it is possible to choose the desired affiliation platforms. Microsoft 365 integration provides access to PowerPoint and other office tools in addition to screen sharing. They are easily displayed as screenshots to be placed in the room. A web browser is also included in the Spatial system. Documents with pagination also allow scrolling (there is no need to import page by page into Spatial, making it easier for other visitors to the scene to read).

CONNECTING

Furthermore, in the context of the Worshop planned in the premises of ENSA and in the context of the in-depth experiments on Spatial at CRENAU, we can see that the quality of the Internet connection is far from anecdotal in its handling. The application depends on this parameter, which can also have its advantages (availability of a Web version that is easy to access on all types of browsers).

Indeed, connecting to Spatial at school and in the laboratory – the main test sites – is sometimes complex. The system is blocked on the computer, and some wifi systems do not allow total freedom of access to this type of platform. This is also the case for many coworking spaces, because of the data protection imposed by the charters on the security of computer systems. These do not provide easy access to browsing, and this is a problem to be considered in an educational or professional setting where the wifi network is often protected. This therefore requires additional communication with the local IT department in order to give access rights to these sites deemed « non-compliant » – the compliance criteria being equally open to criticism as they are lacking in what education can offer these days. On the other hand, there are several cases of incompatibility on Android phones, including phones from relatively recent generations: a message appears when downloading « your device is not compatible with this version ». Browsing a simple Web version is therefore not possible on a phone if the user does not have a compatible phone: the Web version on a phone loses its interest for the mobile experience (downloading the application is mandatory). Nevertheless, in this specific context and under the right conditions, the Spatial experience is extremely effective on the phone. The application is adapted to the small format in a simple navigation, it allows face to face and privileges social interactions in its experience. The universe design is not adapted, however, as the computer version allows more flexibility. I note however that the fluidity of navigation is also interdependent on the time of connection; linked to a rush on the server (French time: 16-17h).

With the Spatial application, it is also possible to try out beta versions, i.e. new functionalities before their official release, with the aim of communicating with the developers on possible improvements. There is thus a desire on the part of the platform to improve its user experience in order to make it available to the general public. One of the tests is for mobile phones to experiment with visualization simulating a VR view without a headset. The movement of the phone would coincide with the movement in the room increasing the immersive feeling.

Spatial presents other difficulties of use: at first it is rather difficult to import personal content (the headset being connected to the Facebook account and working in autonomy), the personal content is connected to Google Drive via the headset, it is necessary to deposit content each time on the drive; with each change it is thus necessary to remove the element and to import it again in the drive. In addition, despite the affiliation of the headset to the personal drive, not all the files appear (often, they are only the latest), and the drive is not always well updated. Other concerns are inherent to the use of the Oculus: connecting the headset itself to the Facebook account is not always easy; it is not very instinctive and the process is long and frustrating.

THE ANTICIPATED LIMITS OF THE EXPERIMENT

Certain limits of the exercise are foreseen in the light of the individual test carried out before the workshop. The difficulties linked to the handling of the VR tools and the daily « objectives » (due to the reduced time of the workshop) that the students give themselves, can generate frustration or discouragement from the VR experience. In order to limit this effect, it seems necessary to specify to the students that the priority is not to produce a finished object but to experiment with the tool in its creation process. Given the conditions of the experiment, each participant will not have a headset at his or her personal disposal during the entire design phase, and the first attempts will certainly be made mostly on the more familiar computer screen. It is certain that the experience of this metaverse platform is part of a hybrid approach but a vigilant awareness remains to be maintained as to the real appropriation of VR equipment by the students. Certainly, this platform has a quality of inclusiveness of supports: people who do not have the headset can continue to manipulate the objects in the scene and collaborate in the project. But isn’t this quality a trap when the equipment cannot be made available simultaneously for each student? On the other hand, does the need to share the equipment represent an added value to mutual aid between peers? We will closely observe these strategies during the different experiments in order to confirm or deny this reservation.

The criticism of a gadget effect can also be formulated. The set of objects available in advance have an undeniable playful character, they reinforce the interactions between users, strengthen a feeling of great potentiality and fuel the ease of handling the platform (in the manner of a camouflaged learning process, one learns to grasp the objects, one moves them, one modifies them…). However, this fascinating effect can be complex to channel, as the predefined possibilities can open up the field of creative possibilities as much as limit it to preconceived objects.

e. Summary: OBSERVATION REPORT

The impact of immersive virtual environments on architectural learning

DAY 1: 21/02/2022

choice of groups within the short project, constitution of a group of 8 students.

DAY 2: 22/02/2022

At 10am, the students spontaneously sit around the same large table. 6 students are counted in the classroom, 2 are in the distance learning class. Each one works individually on his computer, verbal exchanges between students are quite rare this first day, students discover the possibilities of the platform, start their modeling project on the software of their choice (SketchUp, Blender, Rhino…).

Some choose to create confined environments, others experiment with large spaces (desert, landscape, urban scale…). The teacher carries out a briefing with the students in order to specify which types of universe and which types of circulation can be envisaged for each proposal.

The part taken differs according to the personal project and the desires of each person, the question of a photorealistic or surrealist rendering is raised for each idea.

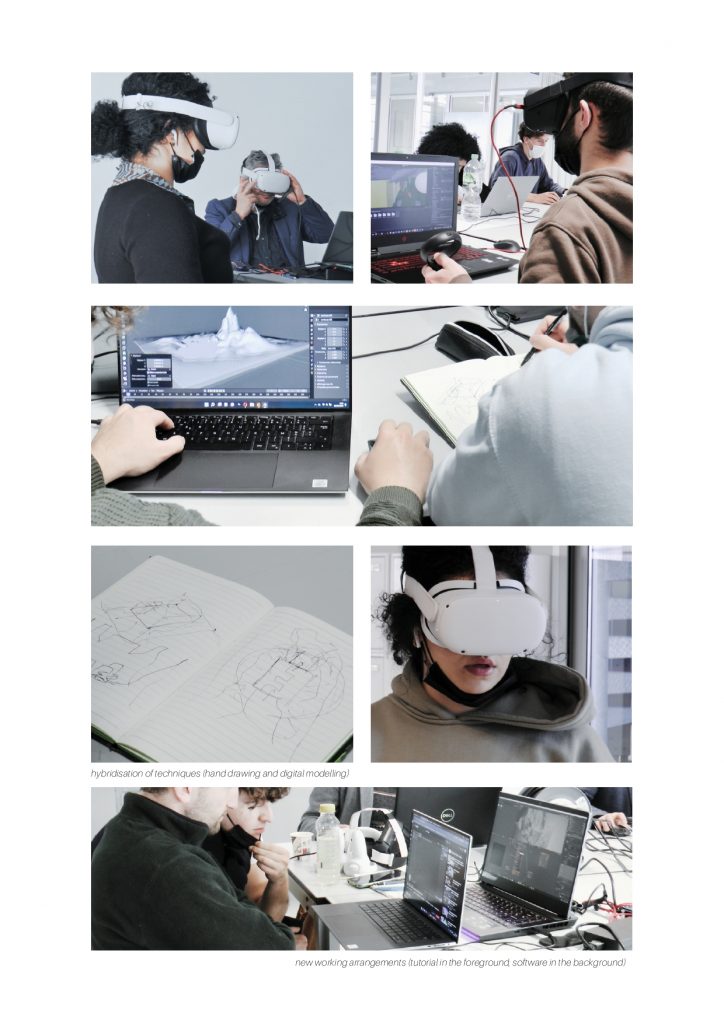

Several strategies are put in place in order to get to grips with the 3D modelling tools. Louis explores for example SketchUp to apply textures. In this respect, Laurent gives the students keys to using the Simlab software (managing lights and textures). The students learn new techniques by manipulating the software by themselves, the term « baking » although unknown for the students is for example quickly integrated in order to apply textures to the volume before importing it. The texture is simplified and integrates the light parameters. The free online object and character bank MIXAMO is discovered by the students in order to import animated .obj.

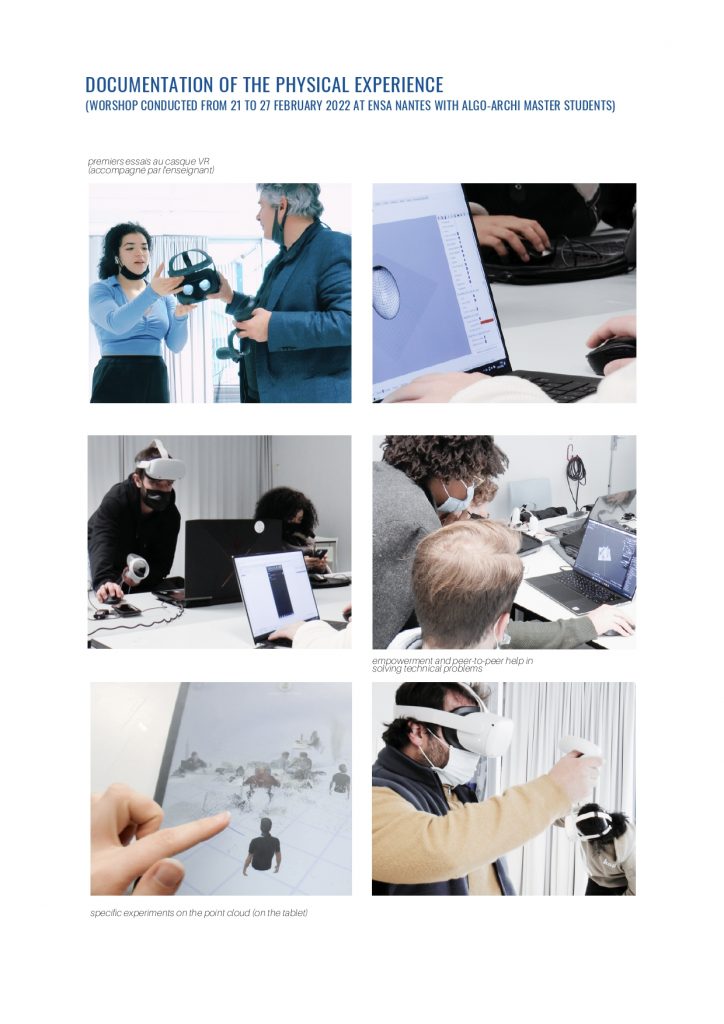

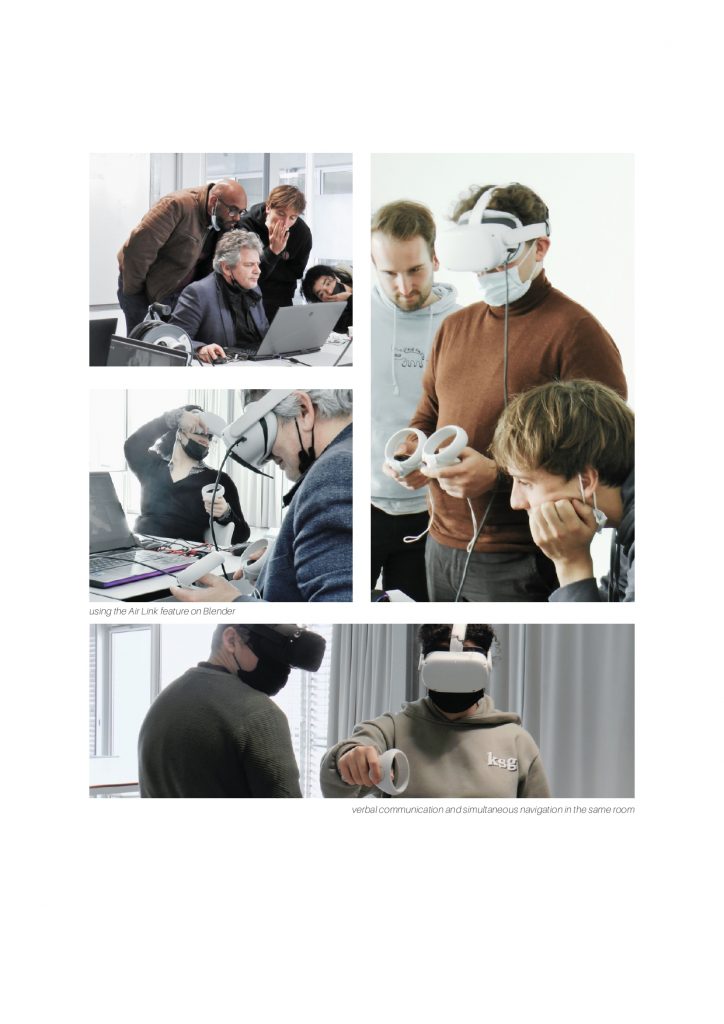

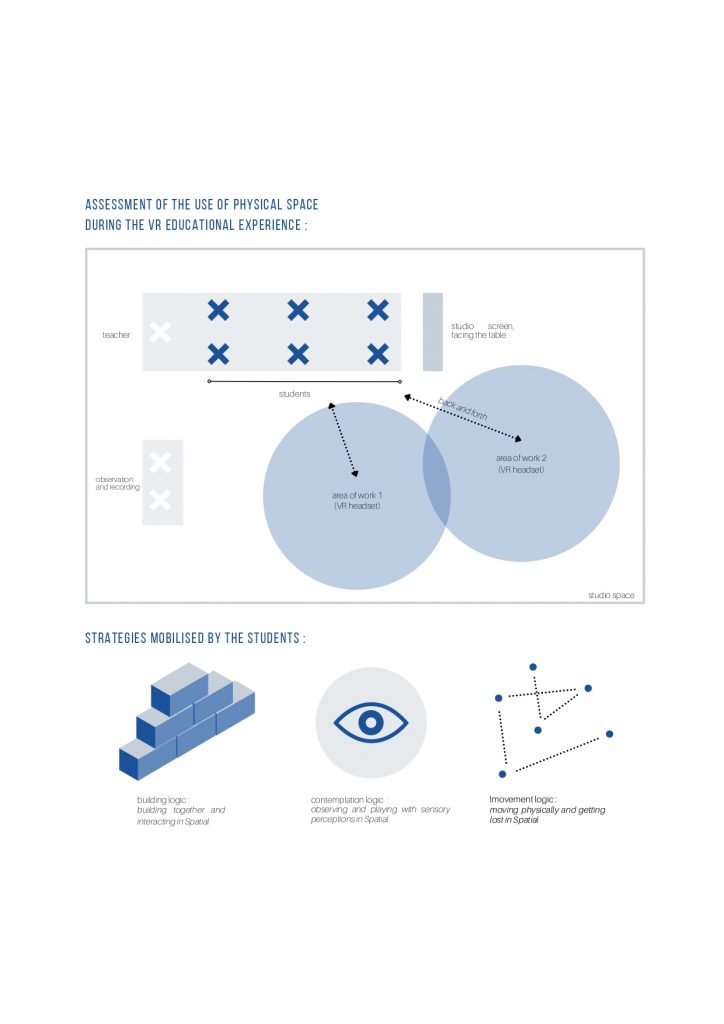

The students are seated around a large table, each on their own computer, and two VR headset work areas are defined next to this table. Several tentative back-and-forths begin between this computer work and the use of the headset, requiring some physical space around them to work freely. Only half of the students are handling the VR headset at this stage.

The teacher is placed at the end of the table to discuss and answer students’ questions. There are many requests to the teacher. Occasionally, several people gather around the same computer to answer a question shared by several students. Technical questions regularly arise in order to ask for help from the teacher. Several criticisms of the platform are made, such as the texture rendering or the limited import weight. Not all students explore the Spatial platform directly, preferring to focus on advanced modelling, on software they are familiar with.

The nearby headset allows them to go back and forth in the Spatial application, in order to compare the effects projected during the 3D modelling and the rendering obtained in VR on the platform.

The students explore several project scales, from the object to the urban scale, their work strategy is mostly individual. Louis proposes to import a 3D map of the city of Nantes at a reduced scale into Spatial.

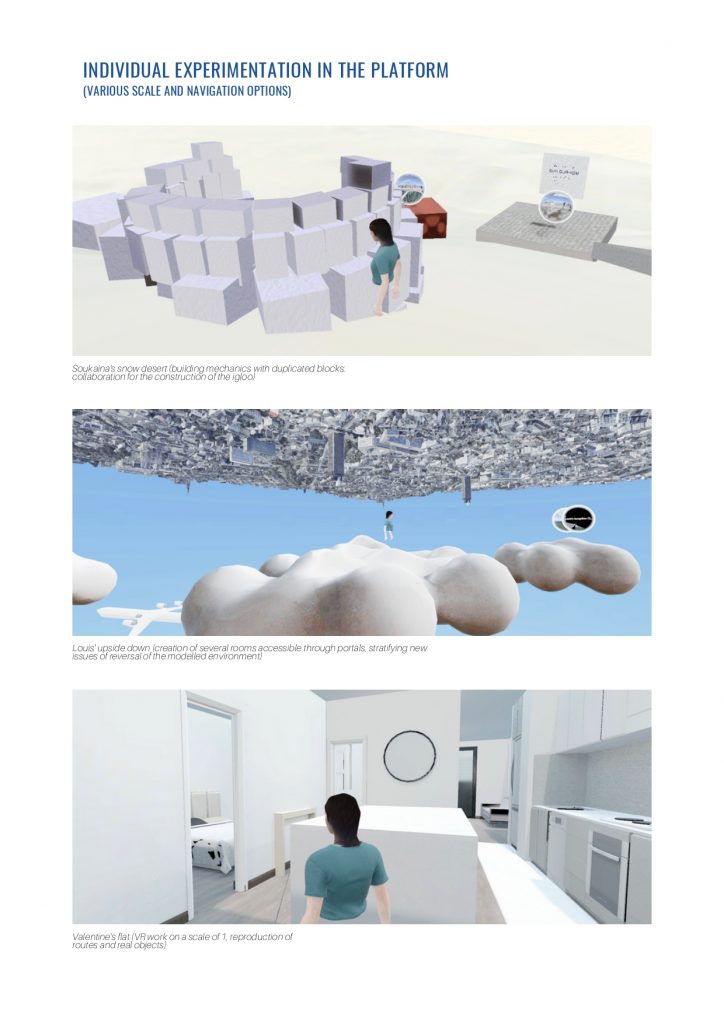

Soukaina explores a modality in Spatial: that of real time design, she thwarts the fragmentary mechanics of the ceiling by importing several of the same building blocks. She thus modelled paving stones intended for the collaborative construction of an igloo and experimented with its construction using a VR headset. Several difficulties were identified: the manipulation of object elements with virtual hands is complex to master in Spatial. The rotations according to Y require to get closer to the object by plunging the virtual hand into the cube. During the construction of her igloo, this is a major difficulty encountered by Soukaina to manipulate her blocks working in modules. The flexibility allowed by the VR headset is however hampered by these impossibilities in Spatial. Duplicating the same block is quite difficult, the flexibility of manipulation becomes a constraint when positioning the modules (grabbing and moving them changes the scale, orientation,…).

It is also necessary to create a solid ground in order to qualify an element as « environment ». This type of learning is carried out by the students through a lot of trial and error at the beginning of the week.

Students are also invited to document their work during the week and to create a « work in progress » room. However, students do not use their room as an in-process workspace, they only use it as a scenographic presentation space. They do not really use the existing objects in Spatial, preferring to import their own models or .obj from other platforms. 3D models on software and digital images are for the moment the only tools used by French students. The latter also do little browsing outside their personal room. Concentration on the whole experience of the day is difficult for the students, as many parameters to be taken into account are integrated in a short time.

DAY 3: 23/02/2022

7 students are in the classroom, 2 in the distance learning room.

At the beginning of the day, the decor constituting the collective room is under discussion by the teachers. Indeed, the students do not really appropriate it, which proves to be problematic for the experience because this room represents the link between the various personal projects of the French and Indian students.

The room is redesigned by the teacher into a more abstract setting to allow the students to organise it.

At 10:30 a.m., a meeting with the Nirma school is scheduled. The arrangement of a collective room all together is envisaged. However, the students find it difficult to plan a collective scenographic project from a distance in the time available.

The students continue their research on Simlab, Blender or SketchUp according to their individual preferences. A 3D scan test was carried out at the request of a student (point cloud on the tablet). Lauryn wants to recreate the studio room on Spatial. The concepts are very varied. Valentine explores a full scale flat in real time. A large « guardian » space is defined with headphones in order to move physically, without fast navigation with the joystick.

A working pair is formed between Yves and Valentine working on a common labyrinth project. Some people work in great autonomy, others are more in the exchange between peers (Soukaina, Medhi, Yves/ Valentin, Louis).

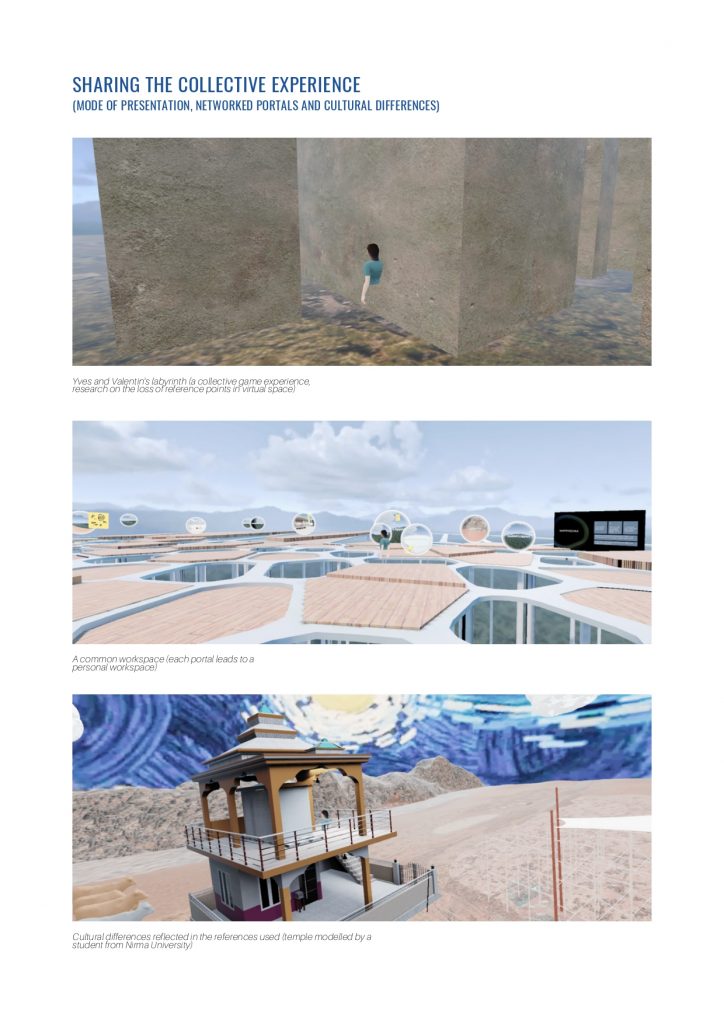

The navigation in the different rooms is also more fluid. Students leave their personal space, explore more the rooms of others thanks to the collective space « Matryochka ». These navigations are made possible by portals positioned by the students. Some students experiment with portals within portals (the « Russian doll » effect described by Laurent Lescop and Hadas Hoper) in order to lead to different rooms which they design as scenettes.

However, there is little collaboration with India. The work is done at a distance and the presence of Indian students in parallel is disembodied. The teachers are considering a meeting by video Zoom in order to exchange between students from one country to another. Soukaina asks questions about the proposals of some Indian students (what format, what weight, how to compress, etc.). But the language barrier does not allow all the students to dare to exchange more fluently.

The VR headset is increasingly used by students. However, students’ attitudes towards the VR headset are uneven. A third of the students mobilise the headset extensively during the design phase (Soukaina, Medhi go back and forth between their computer and the headset, they work by hybridising their methods, they carry out checks in VR as they go along), others wait until they have completed their object/detailed environment before using it as a final rendering. The latter do not directly confront the issues related to perception in VR. Moreover, depending on the project intentions (manipulation in brick time, contemplative environment, abstract landscape,…), the degree of physical involvement during the design process is changed. The interaction with the virtual environment during the design process depends on the intended use of this universe in the headset (walking around, looking, manipulating,…).

The sitting of students around the table does not encourage some to hybridise headset design and computer design. Others are more mobile, exploring the possibilities of articulating these tools.

It is sometimes easier to discuss around the same computer or to pass the same headset to exchange around these technical issues / discussions around a conceptual idea. We can observe that many students explore a relationship with the loss of reference points on Spatial through projects of labyrinth or frozen desert.

A remark is made by Soukaina experimenting with the desert: it is a pity not to have a « Map » or a plan map in order to locate oneself and others in large environments.

On the other hand, the texture renderings in Spatial are not always accurate. The Indian students’ attempts explore, in comparison, larger spaces, circulations and very wide paths. However, their textures are less convincing (the model requires more compression).

One quality that the students noticed was that the play on levels (steps, reliefs, etc.) allowed them to gain height and create depth and hiding places in a landscape.

Learning by observing other peers is also a quality of this experience: going to see other students, comparing possibilities, intentions and techniques of others (and comparing possible cultural differences).

In general, students become more comfortable and less reluctant to explore with the VR headset, and they ask more of the supervisors to use them, or handle them themselves.

The Yve-Valentin pair working on Blender uses paper sketches for the first time to think together. This need to communicate on the same project enriches their collaboration and understanding of the project. The 2D reflection rarely occurs during the experience, the students mostly turn around their 3D model in VR and on the computer. The need to call the teacher for technical concerns on several occasions does not prevent the students from helping each other and thinking about modelling strategies together. They also use the Air Link tool on the headset to manipulate in Blender. The effect produced by the textures is very realistic but the difficulties of importing into Spatial remain a handicap for sharing their work. The pair collaborate around the same computer but other students working individually also engage in discussions to think about an effective design process. The successful trials of one student help the others to gain time in mastering the new tools.

DAY 4: 24/02/2022

7 students are counted in class, 2 in distance learning.

The St. Louis studio room is reproduced in the form of a room with links to other rooms and an urban model in the centre. This arrangement is part of a pedagogical approach, that of sharing the French group’s working environment with the Indian students. Louis explores a room within a room. Each room has an altered reality, the first is an upside down, the second a miniaturised reality,… The visitor walks on clouds, the urban plan in relief is in the air (this is a new use of Spatial, revealing an unreal perspective of a space well known to French students: the city of Nantes).

Medhi’s use of the helmet is very fluid, he takes the helmet off and puts it back on while sitting at his computer in order to work in his 3D model with great flexibility. Medhi is considering the construction of a cave, which requires negative thinking. From a technical point of view, it is simpler to subtract material than to fabricate it around the galleries.

For the moment, the collective presentation space is not very well developed. Each person works on his or her own space to give concrete form to his or her personal idea. The cultural differences in the appropriation of the platform are noticeable, the students of the Nirma school conceive for some temples, markets, colossal wire structures… The size of the structures is impressive. The French students mobilise other references such as the western flat, several universes are suspended in the clouds. The French students favour sensory effects (loss, vertigo, reversal, etc.), while the Indian students favour the possibilities of structures or large built spaces. The relationship to scale is a major issue: the latter apprehend it in its maximum possibilities. This raises several questions: the way of approaching an assignment, the liberties taken by the students, the perception of « what is expected of an architecture student », the cultural differences, the type of teaching in architecture… all this conditions a different relationship to experience and such varied proposals. A video exchange on the studio screen allows discussions with Nirma.

It is increasingly easy for students to focus on the long time of the experience and to sustain their attention to the VR headset, and use it when needed. The idea of two rooms per person is not finally grasped by the students, and few students work directly on the design in Spatial (except Soukaina who makes directly in her virtual space, and invites the other students to collaborate live). The majority develop their concept on a different software and import the finished environment into Spatial.

At 2pm, an experiment is conducted at Coraulis coordinated by Hadas, about urban wellbeing. Several video environments are projected, and students are invited to answer questions about their personal feelings about a street they walk down as a pedestrian.

DAY 5: 25/02/2022

7 students are counted as face-to-face, 2 as distance learning.

On the last day, the students finalise their individual spaces. The models are completed, numerous headphone tests are conducted to finalize the spaces of each. The pair Valentin and Yves try to solve technical problems related to the import in Spatial. The rendering of the textures is inferior and the navigation lacks fluidity, however the model is fully visible in Spatial – which allows the experience to be shared in the platform. Yves and Valentin are working in an unprecedented way on two computers simultaneously (2 screens placed one in front of the other). One of them broadcasts a video tutorial, the other one allows to manipulate the modelling on Blender as you go along.

The navigation between all the rooms is integrated by the students, they navigate willingly in the spaces of the others. After a few days of mastering the VR tools, the students become experts and teach in their turn. It is striking to observe how quickly the students appropriate the tools made available to them (including the students who initially mobilised the tools they mastered).

research report by Marianne-Eva LAVAUR, CRENAU AAU Nantes (accompanied by Laurent LESCOP, Professor, HDR – ENSA Nantes)

31/ 05/ 2022

0 commentaire Laisser un commentaire