The potential of metaverse platforms : pedagogical applications

(prerequisites, experiments and limits)

This report includes the state of the art of metaverse platforms in their educational and creative possibilities in VR – intended for higher schools of architecture, design and engineering.

What other meta-verses platforms have potential for pedagogical application and what are their limitations?

The first step is to explore the different existing metaverse platforms that lend themselves to the pedagogical conditions envisaged for the research.

For the study of the different platforms, we believe it is important to define a systematic methodological framework that will show the following

– Real-time tests describing the functionalities and limitations of the considered platforms, (previously done for Spatial.io),

– Existing literature,

– Survey of schools (architecture, design, engineering), checking whether schools use VR platforms, and for what purpose.

We thus proceed to a verification based on the postulates and remarks raised during the Workshop experimentation. The students’ reactions, their apprehension of the platform as well as the possibilities deployed and limits identified during the experiment, feed the orientation of my research on the existence of other possible platforms applicable to pedagogy. Several verifications are also to be conducted :

Is Spatial finally a suitable platform for the experiment we had planned?

Are Microsoft and Facebook developing metaverses that can be applied to education?

Zoom is planning to open a platform similar to Spatial.io in the near future, what does it offer?

How many users can be in the same room simultaneously?

Do the different platforms under consideration offer several levels of design, i.e. several layers of projects?

What experience can be described in creating an avatar on other platforms?

Are connections with other platforms simultaneously possible (complementary applications, etc.)?

. . .

We were able to define the limits and difficulties encountered by exploring, first of all, the web platform available in VR: Spatial.io. By experimenting with its functionalities and with regard to its use in the design, we can notice that the system includes extensions. Each application is specialised and allows new functionalities in their interweaving with the basic platform. As such, the design of the 3D objects itself requires additional software to design the projected spaces. Spatial.io offers the conditions to host fragmentary objects but does not propose to design or modify them in real time (or in a thwarted way, which is not always accurate). We could conjecture on possible extensions of design software used by architecture and design students. These extensions would allow – as Spatial.io proposes – a scenographic immersion of the space or object designed by the students. There are indeed Add-on or Plugin specialised in the rendering of realistic images, but they do not deploy the collaborative or immersive aspect in the same way. Revit or Archicad are software programs frequently used during architectural studies that work in BIM and allow navigation between 2D and 3D. The possible back and forth between these two dimensions is an interesting asset from a pedagogical point of view in order to multiply the analysis and design tools. However, in view of the challenges and the deployment of current tools, could we envisage extensions of these same software packages in virtual reality? (e.g. Sketchup Viewer offers VR visualisation; Lumion, Twinmotion or Enscape also have VR functionalities).

a. INTRODUCTION TO METAVERS : origins, fate of social networks and heterotopia

First of all, the Metaverse is a new type of web application with a social character, which incorporates a variety of new technological possibilities. Metaverse platforms offer an immersive experience based on virtual reality technology, generating a parallel vision of the real world based on a form of « digital twin ». From an economic point of view, metaverses develop a commercial system based on the blockchain (a system recording virtual commercial transactions), a social system through various events and interactions, and an identity system, where each user can personalise his or her appearance as an avatar and his or her environment in digital space. However, the metaverse is a concept that is evolving at a high speed; users are enriching their issues through the creativity they develop in these meta universes. It catalyses several desires: that of extending the Internet to mixed reality (virtual reality, augmented reality, artificial intelligence), to the deployment of a faster network (5G/ 6G), and to the development of an innovative communication axis for social networks.

The very first terms evoking the notion of metavers come from science fiction literature: « The term first appeared in a 1992 novel, The Virtual Samurai by Neal Stephenson, to describe a computer-generated universe accessed through glasses and headphones. [Metavers are part of the field of virtual reality (VR) that emerged in the early 1980s and is based on an immersive representation of a virtual environment that the user can interact with to move around and perform various tasks. The richness of this representation and interaction generates a sense of presence in the virtual environment that promotes user involvement. » (Pascal Guitton, Nicolas Roussel, What technologies are metavers based on, The Conversation, Published: 25 February 2022 https://theconversation.com/sur-quelles-technologies-les-metavers-reposent-ils-177934) The presence of the platform generates a sense of presence in the virtual environment that promotes user engagement. Facebook’s announcement in 2021 to expand its Meta universe, has highlighted to the general public the existence of these types of platforms, which are largely unknown. The general characteristics of a « meta » universe are the following: the presence of virtual environments, landscapes or settings; these are accessible through digital interfaces (computer, tablet, phone,…) or specifically adapted to VR use (headsets, mats,…) – allowing an increased perception of sensory parameters; the presence of interactions between several users through avatars (collaborate, cooperate/compete, exchange, move, contemplate,…). Launched in 2003, the Second Life game founded by Philip Rosedale, prefigures the Meta universe, and in 2007 had nearly 2.7 million subscribers. Political debates, concerts, reading groups, exhibitions, seminars, academic courses, wedding celebrations, sale of virtual objects, existence of a specific currency, etc., the game develops what Facebook will call fifteen years later « the future of the Internet ». This Web game constitutes one of the first successful and popularised forms of « Multi-user Virtual Environments » technologies: MUVEs (followed by other platforms such as World of Warcraft or Active World in the 2000s, allowing strong collaboration between players to achieve common quests). (cf: Ishbel Duncan, Alan Miller and Shangyi Jiang, A taxonomy of virtual worlds usage in education 2012, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2011.01263.x) For two years, Tom Boellstorff, the anthropologist in charge of the investigation on the platform published the book « An anthropologist in Second Life. An experiment in virtual humanity », drawing lessons from an efficient and functional networked metaverse. The platform must be manageable and easy to manipulate by a larger number (its difficulty of handling having been a major brake on its greater expansion for some novice users), the need to give free rein to the platform’s users in the customisation of their environment (all of the elements designed in the game were indeed the result of the creativity of its users and their collaboration), the need to create a secure space (encouraging responsible behaviour in order to preserve a secure space, and to verify the identity of users). « The metaverse is something of a paradox, both an inhabited and enacted space as well as an impermanent interface between the digital and physical realms – an expression called ‘phygital’ in contemporary investigation into experience design (Gaggioli, 2017). » (David van der Merwe, The Metaverse as Virtual Heterotopia, World conference on research in social sciences, Oct 2021) The increased interest in the development of metavers is intrinsically linked to the issue of the future of social networks (owned mainly by the GAFAMs Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft). Blockchain technologies are growing rapidly on this type of platform: the communication tools that these networks represent have a multiplier effect on the general public’s interest in these devices. We can ask ourselves whether metaverses constitute a new form of spatial and social heterotopia (heterotopia defined on http://geoconfluences.ens-lyon.fr/glossaire/heterotopie « A concept theorised by Michel Foucault during a lecture at the Cercle d’études architecturales given in 1967, heterotopia designates the differentiation of spaces, often closed or enclosed, characterised by a discontinuity with what surrounds them. The term is forged on the Greek roots expressing difference or otherness (ἕτερος) and place (τόπος), but also on the word utopia. While utopia offers an ideal ‘without a real place’, heterotopia corresponds to a real place (Lévy and Lussault, 2013). Heterotopia generates differences in behaviour, deviations from the norm or the creation of new norms, access to new freedoms or the respect of new rules or constraints »). This question is also raised by David van der Merwe (David van der Merwe, The Metaverse as Virtual Heterotopia, World conference on research in social sciences, Oct. 2021) mobilising the notion of ‘da-sein’, the being-there attentive to others and the environment in which we find ourselves. How should these non-places [metaverses] be governed, financed and regulated or whether their virtual nature excludes them from these ‘real life’ (RL) constraints. Furthermore, the amount of time and effort invested in these blockchain-powered meta-verse environments and the construction of virtual identities to inhabit them – via online social networks, games, commerce, blogs and the like – lends credence to the relative importance of these environments to RL interactions. The Heideggerian concept of Dasein can then be applied to the metaverse and its heterotopic nature to question the broader concerns at stake regarding the essential nature of the person and relationships within the metaverse. « (David van der Merwe, The Metaverse as Virtual Heterotopia, World conference on research in social sciences, Oct 2021) In the field of architecture and design, the potential uses of VR applications are wide: from the design itself, to the construction and communication of the project and collaborative decision-making. The manipulation of virtual environments during the design process directs designers towards a finer visualisation of the space they are designing in its different dimensions – fluidity of circulation, efficiency of its use, precise functioning of technical details,… in addition to 2D representation tools. Moreover, the Unity and Unreal engines are increasingly considered for applications in the fields of architecture, engineering or cinema. These metaverse platforms should therefore be considered with great attention, with regard to the potentialities they offer but also to the abuses to which they may unfortunately be subjected. It seems relevant to underline the unprecedented conditions in which these platforms have been able to expand. The Covid pandemic has initiated a renewal of technical and digital means to compensate for the impossibility of physical meetings to plan activities, collaborate and communicate despite the distance.

b. Why mobilise these metaverse platforms as an architect ?

Apart from projections in the entertainment world, we can legitimately ask ourselves what public uses these virtual reality spatialization tools if architects do not use them? It is important to be vigilant when using these platforms as architects, as it is certain that other trades or companies will appropriate these tools with different ambitions. These debates are linked to real estate concerns for example: in peri-urban areas we can question as architects the spatial qualities that real estate developers offer to users of suburban areas – and the profit that this can generate in the absence of development policies and fine tuning of these territories. The interest in these land resources is indeed highly capitalisable, in the same way as the new possibilities developed in the meta-worlds. We can observe this with the expansion of NFTs, available in these meta-world platforms, confirming the economic model towards which these platforms are heading, taken over by GAFAM. The architecture industry is rather late from a technological point of view (as a comparison in object design and shipbuilding industry, the use of immersive tools is already taken with more attention). Furthermore, VR is an additional tool to design but is probably not to be abstracted from the architect’s other techniques. A balance is certainly found in the mixing, the back and forth between equipment, techniques and modes of visualisation of the architectural project. Currently, the use of computer-aided design (CAD) software by the construction industries is no longer an innovation, but a real necessity (particularly in its inclusion in the educational process of architectural design). The development of digital tools for parametric and algorithmic modelling as well as the technologies developed for human-virtual environment interaction in a sensory immersion space, represent potential applications for the architectural field. Virtual reality (VR) applications allow new modes of mobile visualization, presentation of panoramic views, etc. Mixed reality (MR) technology is also developing to enable the enhancement of digital images produced to reproduce real-world effects (in the case of photorealistic rendering images and immersion in these architectural and living environments). As Agnieszka Gębczyńska-Janowicz points out applications to the field of heritage and rehabilitation can also enter into dialogue with these new tools (in a preparatory phase of design in order to test contemporary proposals consistent with the existing urban and architectural fabric in an immersive environment):

» The introduction of virtual reality to classes in the conservation of monuments or designing commemorative architecture combines aspects of the past with a contemporary understanding of the world, while respecting history and heritage. The synergy of contemporary technological development and historical knowledge provides an opportunity for students to prepare for the growth of digital technologies and, what is more important, to acquire additional competencies fit for their future careers. « (source: Agnieszka Gębczyńska-Janowicz, Virtual reality technology in architectural education; Gdańsk University of Technology Poland, 2020)

Furthermore, the current development of meta-versus-object interfaces is directed towards perfecting the sensory perceptions of cyberspace, simulating senses other than sight. Thus the choice of the immersive device and the platform used – i.e. the mode of transmission of these perceptions – deserve to be put into dialogue in their applications to design; the perception of these virtual environments would then constitute a spatial experience that is no longer objective but sensory and complete. This intrinsically raises the question of the relationship to the destination of the constructed work: is it preferable to create « reconstructed worlds » within these virtual platforms in order to anticipate real applications to the experience, or is the virtual experience a work in its own right destined to exist in itself? It is clear that these two possibilities can coexist or be destined for deferred uses.

The strength of the global network enabled by the operation of these platforms also represents a large-scale laboratory in which subjects with very varied social and cultural profiles interact. This parameter should be taken into account for the design and planning professions, whose design destination is at the heart of questions of use and adaptation to the social context. « The Metaverse is likely to be able to provide the audience with more believable data from the world. This will occur by using the many possibilities of simulation. As a result, it would have a deeper effect on the interpretation of the real world. (Hemmati, M. (2022). The Metaverse : An Urban Revolution Effect of the Metaverse on the Perceptions of Urban Audience, Tourism of Culture, 2(7), 53-60)

c. What can we learn from entertainment? (sampling of notable platforms and projections towards pedagogical and conceptual applications)

The example of Open Worlds designs including the physical body or immersive systems applied to video games, can be a lead towards new networked creative processes. In the field of game-design, the existence of platforms and treadmills like « VR treadmills » constitute additional immersion devices for players in order to increase the effects of VR. e.g.: Virtuix Omni One, Kat, WalkCyberith Virtualizer, Infinadeck, etc. The sensation of effort, even if it is slight, does contribute to the intensification of the feeling of immersion. However, in order to ensure comfortable handling, the effort cannot be equivalent to what happens in the virtual world: the character engages a higher physical effort that is unbearable for the user. These, like the VR headsets and glasses developed by several brands (Oculus, HTC, etc.), aim to massively colonise the living rooms of the general public. Nevertheless, considering the price of this equipment and the space required for its installation, we can wonder about the real inclusiveness of such devices. Indeed, this raises the question of the destination and who can access them (apart from people with a physical disability). At present, access to VR is a privilege, which also explains why most universities do not always invest in these initiatives. Beyond the financial cost, a form of erudition is still required to take advantage of these devices: it is a question of installing them, mastering them, having the necessary space to use them. This requires a financial and spatial resource that individuals and higher education institutions do not always have. Also, the argument of accessibility for a larger number (often stated in the current pandemic context), is a flawed argument.

On the other hand, as we can observe and experience for ourselves, VR has drawbacks in some incomplete applications, subject to research. Using a headset causes nausea for 30min to 1h in a common user due to the disturbed perception of motion in the inner ear. « The problem is that every time you move in VR but your head or your real body doesn’t move, it ends up making you sick […] it’s a terrible problem if you’re trying to create a social experience, » Philip Rosedale. (Source: KEN KOYANAGI, interview with Second Life inventor Philip Rosedale for NikkeiAsia, 18 March 2022)

However, the management of the time of use is a parameter that is supposed to be flexible for the user: the experience must in fact be interrupted to limit discomfort. These inherent technical problems raise questions about an effective and sustainable pedagogical scope over the time of a workshop. If a course is accompanied by VR, the configuration of the workshop itself must be adapted in order to provide the breaks necessary for the well-being of the students. Thus, as we have been able to verify, VR does not completely free itself from physical limitations. Is the wall visible, is it suggested by a limit in the player’s movement? How does the user understand the spatial limits of the game, of his or her avatar, of the room in which he or she is? The finiteness of space thus also catches up with users in the virtual world. According to a study conducted on the psychological relationship to the virtual body concerning the interpersonal distance between avatars, we can also note that the physical embodiment of our own body raises the question of the finitudes of space. Users who are put in a situation of discomfort in virtual space by the exaggerated variation of these distances return the following emotions: (in order of preference)

1. I felt angry when the virtual people passed through me.

2. I was surprised when the virtual people passed through me.

3. I felt scared when the virtual people passed through me.

4. I would be willing to delete the virtual people so that it would stop.

5. After they passed through me, I would like to take revenge on those virtual people.

(source : Jim Blascovich, Interpersonal Distance in Immersive Virtual Environments, Article dans Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, août 2003 DOI : 10.1177/0146167203029007002) Furthermore, we can remember that designing in a metaverse platform requires learning. « Learning to learn » is necessary before even wishing to design a coherent and relevant spatial ensemble. In the same way as a traditional « low tech » tool, or modelling tools currently taught in architecture, design and engineering schools, virtual reality is a device that could be further mobilised by these schools. Several students – because of their individual interest in these tools – are integrating VR into their practice, but in a very punctual way. On the personal initiative of some students or propelled locally by teachers, the approach is rarely instituted in schools. The survey is therefore necessary to identify these localised initiatives and to question users about their practice. (cf. current survey: Survey on the use of virtual reality in higher education)

In this respect, the need to learn and the time needed to adapt to the handling of a platform can lead us to an answer: Spatial.io is certainly an efficient platform to start experiments such as they were envisaged for the previous Workshop. In the time given to imagine protocols for framing and observing the experiment, it was necessary for the workshop tutors to master at least the primary functionalities of the platform. Once these conditions were met, the students were able to develop other imaginations or to overcome difficulties specific to the use of the platform.

From video games intended for the general public, to cutting-edge urban initiatives, to commercial « serious games », many companies are taking the issue of metaverses to heart and developing various platforms or extensions to their products…

- Minecraft

Recently developed in VR (in creative and survival mode), Minecraft is a game with a powerful collaborative aspect between users: learning takes place through contact with other players in an informal way and through tutorials. In creative mode, the field of possibilities is very wide. This VR functionality is available for Oculus and Windows Mixed Reality headsets. However, Minecraft VR is not available directly from the Oculus shop, an Oculus Link cable, or wirelessly with Air Link or Virtual Deskto is required (as well as a Steam VR configuration). The Discovery app available on Oculus, is a dupe of Minecraft (a block building game), currently being submitted to the Oculus App Lab. The experience seems very similar.

- Creation of a virtual campus: Kenya-KAIST

This will open by September 2023 in Konza Technopolis, 60 km from Nairobi. This metaverse is in line with the vision of certain cities or schools to recreate activities and a parallel economy to the real world (by offering new public services that are complementary or similar to the real world, exchanges of goods, access to certain content/courses, wandering in a virtual urban environment, etc.). « Following a feasibility study of the Kenya campus five years ago, we have planned to use Mooc courses created by KAIST faculty. The use of online content will help to bridge the educational gap between the two institutions and reduce the need for many students and faculty to make the long journey from the capital to the campus. Although students are expected to live on campus, they are likely to engage in other activities in Nairobi and will want to attend classes wherever they are. » (source :Times Higher Education (THE) https://www.timeshighereducation.com/campus/educational-metaverse-coming, octobre 2021)

The argument of inclusiveness in the face of access to education must be qualified: the VR devices hosting this metaverse project are not within the reach of everyone (expensive and technical, despite the desire to make these tools accessible to the general public and thus reach as many users as possible), and hardly seem to replace in their entirety training and services delivered on a physical campus (access to sports, manual workshops, etc.).

- Seoul Metaverse

Seoul aims to become the first municipal government to enter the metaverse, making several public services and cultural events available in virtual reality. The South Korean capital has invested the equivalent of 2.8 million euros in this project, which is part of the « Seoul Vision 2030n » plan. We can wonder about a metaverse trend propelled by the Meta Group’s announcements. The surge of projects announcing the creation of metaverses underpins major political and electoral arguments. This trend, which can be observed on the scale of entertainment (programming of large-scale events) and the economy (capitalisation of virtual goods and spaces), has led to a desire to extend political and spatial concerns into these digital worlds, where the stakes are absolutely high (extension of real urban projects into virtual space, absence of a well-established legislative framework, economic potential, etc.). In a spirit of conquest, we can note a desire to take one’s place before others in the field of metavers, towards a race for the most innovative virtual city of tomorrow. On the other hand, the financial costs involved in such proposals are significant, and projects take a long time to be born (in five years, it is difficult to predict with any great precision whether certain issues raised today will not be obsolete by the time the platform is released).

The article The Metaverse: An Urban Revolution Effect of the Metaverse on the Perceptions of Urban Audience asks: “What effects will the emergence of virtual cities versus physical ones, have on the perceptions of these cities, or more precisely, the urban landscape? ” (Hemmati, M. (2022). The Metaverse: An Urban Revolution Effect of the Metaverse on the Perceptions of Urban Audience, Tourism of Culture, 2(7), 53-60)

These legitimate concerns are an extension of the dynamics of smart-cities, whose desire for technical and technological innovation extends to the creation of a virtual version of their urban model. What the metaverse shows of the city – or its reconstructed version – influences what we perceive of the urban in the real world. An event taking place in an urban space translated into a metaverse is perceived by the observer’s avatar, it becomes part of his mental cityscape. This means that the metaverse can act on the image of the city in a symbolic and concrete way – without even directly interfering with the physical city. The possibilities of ‘what ifs’ (what if the city was in ruins, what if the city was completely decarbonised, what if the city was upside down,…) are endless considering the creativity and the number of users of these virtual cities.

- Baidu metaverse

The Xi Rang universe is a metaverse proposed by the Chinese internet platform Baidu. Developed in 2021, it aims to recreate a simplified networked activity in VR. This metaverse allows users to interact with other people in virtual settings that can be freely explored. Users can visit monuments, exhibitions or carry out activities virtually (video games, entertainment, culture, education, shopping, advertising, etc.)

- VoRtex

Vortex is a metaverse platform under development, created by Microsoft. It is a tool for collaborative learning applied to construction and educational experience. « Collaborative virtual environments (CVEs) are VWs that provide a richer collaborative arena for social encounters and community building. Another name for CVEs is virtual learning environments (VLEs), the universal term in the literature associated with education. Examples of CVEs include social entertainment, multiplayer games, interactive art, simulations, distance learning, architectural walk-throughs, cultural heritage, etc. CVEs can offer many features to students who need support in their learning process. In the serious game domain and gamification, there are initiatives for interconnection with systems such as massive open online courses. Gamification is a method that provides an effective layer to learning in the context of engagement and motivation. » (cf: Jovanović, A.; Milosavljević, A. VoRtex Metaverse Platform for Gamified Collaborative Learning. Electronics 2022, 11, 317. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11030317)

Gamification is indeed a phenomenon that can be observed in many of today’s educational methods, including in the professional world (« serious games » aimed at professional environments are indeed new opportunities for video game developers to specialise). The notion of games is being exported beyond the entertainment world and is colonising academic and technical applications. For school use, we can imagine how secondary and primary school teachers can also seize such tools: a means for families and the teacher to interact at a distance, the teacher can clarify certain knowledge by showing students an immersive 3D environment (regions, countries, etc.), recreate an interactive and playful classroom environment, simulate role-playing of historical events, create virtual scenarios dedicated to learning, live the virtual experience as a complement to reflective learning, etc.

The article compares VoRtex with two other platforms: VX Vircadia and Sansar.

- VW Vircadia

(Vircadia worlds are accessible from Windows, Linux and MacOS, with support for Android, iOS and Quest 2 coming soon). Vircadia worlds are among the largest with 16 km³ of real-time, cooperative building space.

- Sansar

(developed by LindenLab) The application allows users to create 3D spaces, interact, collaborate around games, videos or conversations. Sansar is available for free on HTC Vive and Windows computers. However, the application is no longer available on Oculus Quest 2.

- Mesh

Mesh, designed for Teams, is also a platform created by Microsoft. It allows people in different physical locations to join collaborative, shared holographic experiences with Teams tools. This business tool allows people to join virtual meetings, send messages and collaborate on shared documents.

- Horizon Workrooms

Horizon is also a track developed by Facebook, compatible with the Oculus Quest 2. The platform offers a collaborative work environment. Recent updates offer new environments, customisable posters. However, the system is not very inclusive. Unlike Spatial.io, if other fellow users do not have a VR headset, the experience seems less relevant – the headset provides a specific framework for working. The video calling system is limited as it only takes into account those with a VR headset (the call is on one screen and not on several around the table). This is currently not a majority of people. The « default » environment is quite poor, this seems to be a difficulty in qualifying a stimulating working environment. The meeting rooms are well designed, subject to several updates (as they are often preferred by users), but the import of 3D objects is not possible, so customisation is very limited. There are only 4 working environments available, and objects cannot be moved freely. Furthermore, the Desktop application is only available for macOS and Windows, Linux is not included.

- Horizon Worlds

This is a platform powered by the Meta Group, which allows users to create collaborations with other users, explore virtual worlds, and generate interactions through play. Launched in December 2021, it is currently available in North America (USA and Canada). Its launch in Europe is scheduled for 2022. It has its own virtual economy, and is part of a dynamic on the part of Meta to capitalise on these virtual spaces.

- The Sandbox

This French metaverse is a 3D game based on the Ethereum blockchain. It was co-founded in 2011 by two experts in mobile games: Arthur Madrid and Sébastien Borget. The platform has about 30 million users in total, (source : https://www.realite-virtuelle.com/the-sandox-dossier-complet/)

and is very active in the field of crypto-currencies (possibilities to trade and sell NFT within the platform). Active » users are to be distinguished from players in Sandbox, they create the resources offered for sale on the Marketplace (virtual real estate, digital art content, etc.).

- Decentraland

Decentraland is a platform available in « decentralised » virtual reality. It consists of almost 100,000 parcels of land. The plots are non-fungible tokens (NFT) that can be purchased using MANA (a cryptocurrency based on the Ethereum blockchain). It is possible to create scenes, illustrations, thanks to the Builder tools (participation in events also allows to win prizes). For more experienced creators, it is possible to pay for additional tools to create games for the community.

- VR chat

VR chat is a place to socialise through play and exploration. The application allows the creation of avatars with a wide variety of profiles, and allows the wandering of surprising virtual spaces. The success of this platform lies in its networking potential: it is possible to chat with people from all over the world, many people with VR equipment have this free application.

- Engage

Engage is a virtual reality education and corporate training platform. It allows schools or companies to organise meetings, presentations, courses and events with multiple users. Through the platform, training courses and collaborative experiences can be created in VR (possible distribution of documents and media from OneDrive, Google Docs and Dropbox, PowerPoint videos, websites, videos in various formats, audio / 2D, 3D and 360)

- Mozilla Hubs

Launched in 2020, this metaverse is highly inclusive (compatible with PC, Mac, smartphones, PC VR headsets, Oculus Quest,…). It is possible to create your own work and play rooms, and share content in real time (Youtube videos, websites, 3D models from Sketchfab,…). The advantage of Mozilla Hubs lies in its open source nature (and the possibility to quickly modify what is suboptimal in use).

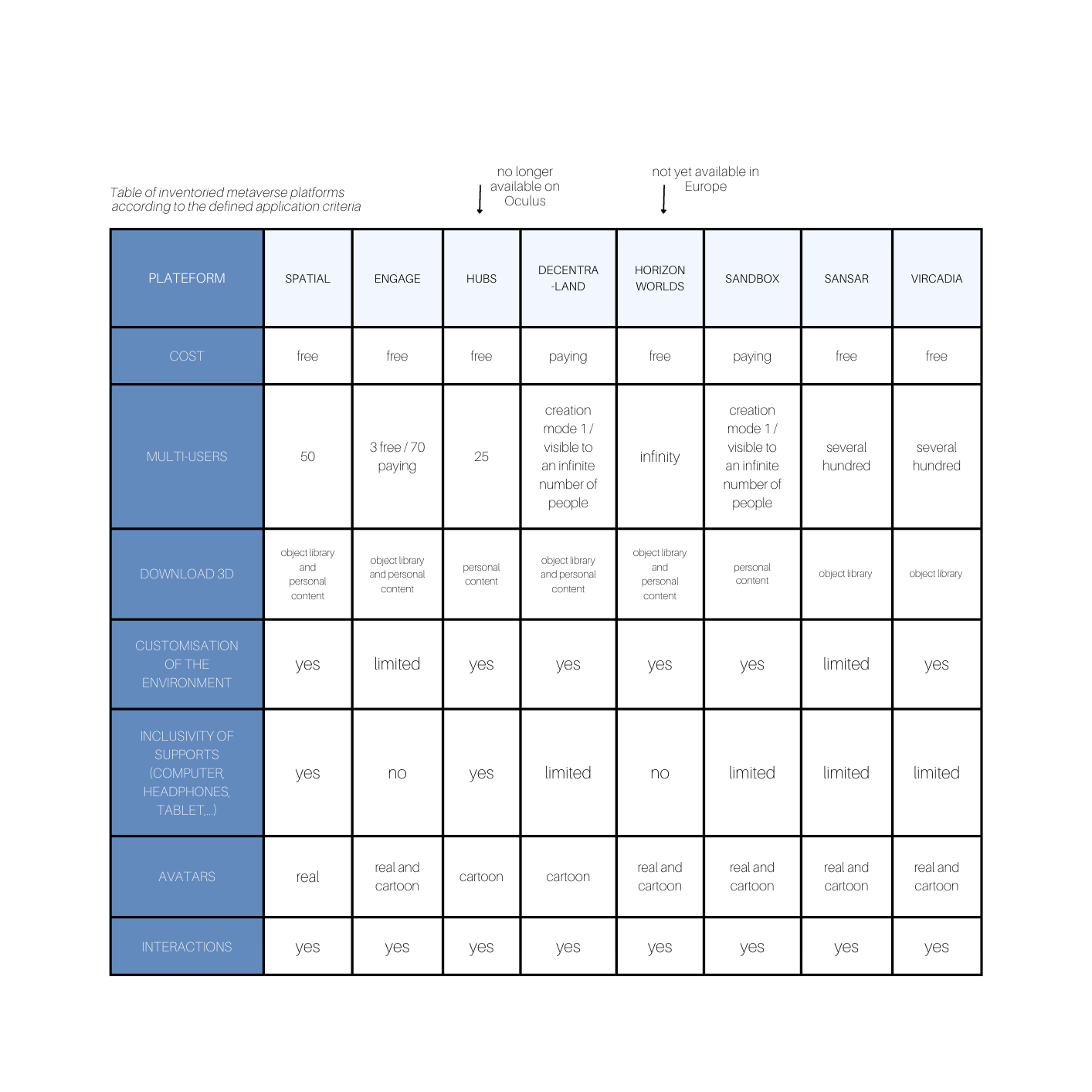

In the state of the art of these different platforms, we can wonder about the criteria determining the selection of those that can be subject to testing. Some are expensive or incompatible with Oculus Quest 2 (the hardware at my disposal). A set of criteria must be put in place in order to select an efficient panel that is coherent with the constraints.

Initially, eight possible platforms are determined according to the previously identified criteria. The following platforms – including Spatial.io previously submitted to the study – are identified : (cf. Table of inventoried metaverse platforms according to the defined application criteria)

However, the difficulty of this subject lies in its constant updating, and the topicality of the new platforms available. In this case, we are looking for possible applications to pedagogy and design. This involves: a modification of the virtual working environment, the creation of a personal avatar, the presence of interactions between several users and the uploading of elements into the virtual space (3D and 2D). Three platforms were initially selected by the group of researchers: Spatial, Engage and Hubs. The Engage platform appears to be suitable for a second phase of testing, however Mozilla Hubs is no longer available on the Oculus app store. A new platform, « Horizon Worlds », soon to be available on the Oculus Quest 2 in Europe, seems to be a relevant avenue for collaboration – although this should be put into perspective from the point of view of the applications we are considering. This platform allows the recreation of group work conditions in workshops, through its numerous 3D sketching and design tools (for example, 3D objects can be modified and manipulated by several people at the same time, which is a new parameter compared to the various platforms identified above).

d. COMPARATIVE TESTING: The Engage platform

ENGAGE is a platform for collaborations, virtually organised events, and virtual reality distance learning. The platform can be used to access open sessions, including courses that are broadcast live but also recorded and replayed. These courses take place in a variety of immersive spaces, customisable with 3D assets from a library of content available on Engage, or user-uploaded models. The courses provide lectures on a variety of subjects offered by the content publishers registered on the platform: in the fields of history, science, language learning, and tutorials of all kinds. The creation of the profile is intended to be inclusive and personalised in order to best correspond to the participant’s use of the platform (gendered or non-binary option, specification of height, age, etc.). The character can be realistic or in cartoon form depending on the option available (with Engage Plus, it is possible to import a photo on the face of the avatar, with the Standard version the avatar can be personalised in cartoon form: clothes, look, morphology, skin colour, etc.). The creation of the avatar is convincing from this point of view, and offers a more embodied virtual body translation than on the Spatial platform (the latter does not offer such a fine customisation). The avatar can be moved with the A button on the controller, using teleportation (similar to Spatial, a viewfinder appears and allows you to move in fast forward), or by natural movement in physical space.

The creation mode is accessible by starting a personal session. It is possible to edit a session alone or in a group by creating an ID and password to access it, using a login system similar to Zoom. A few starting environments are available, but compared to the possibilities offered by Engage Plus – the paid extension of Engage – these environments are not very varied. In contrast, Spatial provides access to a variety of content that is completely free and easy to manipulate on the computer. The computer version of Engage (via the app) is very flawed in various tests, with sessions refusing to open, making it impossible to evaluate the experience without the virtual reality headset. In addition, there is a web version but it is necessary to download the desktop application to navigate on a computer. This can be restrictive given the weight of this additional application (2 Giga). The browser version does not allow access to the content of the creations, nor to edit sessions, it simply allows you to consult the events, register and modify your avatar. The VR experience is more developed than the tools available on the computer, which does not make the user experience inclusive for a variety of media.

Several professional and educational settings are proposed by the platform to host meetings (amphitheatre, meeting room, open space, conference venue…) and other types of leisure spaces (boat, forest, space hotel, waterway, desert landscape…). It is also possible to create questionnaires and forms for educational sessions. Links to websites, Youtube videos or PowerPoint presentations can be imported directly into the virtual environment by entering the URL in the « media » tab. The bank of objects to be imported is also very well supplied to personalise the environment in the form of clickable IFX: everyday objects, animals, creatures, professional elements (board, desk, chairs, etc.), etc. Unfortunately, the import of external content is limited: the paid Engage Plus package offers a greater degree of customisation, and allows the creation and editing of open content for the public. Several events are available every day in the form of Live or one-off events, art exhibitions adapted to the Metaverse, academic or free lectures,… These happenings require a paid ticket to access the content of the artists and speakers. The platform seems to be less and less open to free and royalty-free content, considering its recent evolutions (additional applications, paid packages, Engage Plus options,…). The tablet tool also makes it possible to manipulate the various controls of the platform with one hand, like a paint palette, and thus navigate easily from content to content. This is a more fluid and practical system of use than the return to the menu proposed on Spatial. Several public sessions are also open, and it is possible to join this type of event shared by the host of a session, between several invited people. Like Facebook events, it is possible to signal interest in a particular event or commit to participating. An event calendar lists the events that are scheduled.

Many bugs or freezing problems have nevertheless been reported on the Oculus (impromptu disconnection, frozen headset, blocked avatar, etc.). Initially created for the HTC Vive, the platform has some imperfections when it comes to adapting it to other media. The management of the connection to the platform is also not very fluid: each time the user removes the headset, the application disconnects and takes a long time to load to restore the session. This is not optimised for switching back and forth between multiple tools, or simply managing eye strain. Engage’s multiple planned extensions include Engage Oasis, a paid metaverse for businesses to use as a virtual meeting place for groups, professionals and students – looking for an audience to sell their products, services or various subscriptions. It allows these specific users to build business relationships, and a remote sales network from the meta universe.

Thus, Engage is more professional and educational than Spatial, but does not deploy the same ease and accessibility at the conceptual level. It is less easy for the general public to access free content and edit their own immersive environments with finesse in Engage. The default content offered is certainly varied and customisable enough, but does not have as much freedom to customise its environment without paid functionality. The premium version allows users to access more content, for businesses it also allows unlocking more users per session and other types of professional features.

e. THE APPLICATION OF IMMERSIVE VR TOOLS IN DESIGN

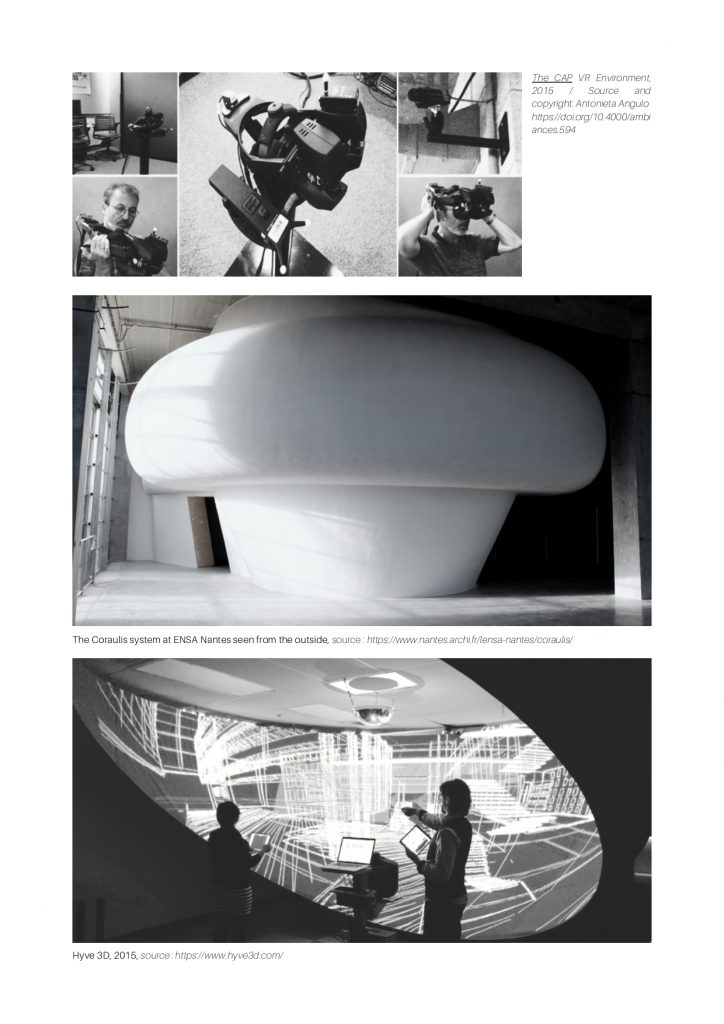

In general, the use of immersive VR devices and platforms has long been limited to a final visualisation of the architectural objects presented. In terms of practice in the design process, it is rare to find a dynamic mobilisation of these tools in the academic environment. Immersive VR environments have potential in that they allow for the accurate perception of materiality and volume representation at various scales of study in the design process. Head Mounted Display (HMD) devices that can be virtual headsets or goggles complement navigational control tools and provide a human-scale visualisation. This also induces a greater sense of body presence compared to visualisation tools using simple projection. « VR systems range in the level of immersion they provide. Immersion is a psychological state characterized by perceiving oneself to be enveloped by, included in, and interacting with an environment that provides a continuous stream of stimuli and experiences (Witmer & Singer, 1998). It is quite well accepted that (physical) immersion or the psychological state achieved by physical immersion contributes positively to the creation of presence. Thus, the immersion effectiveness of a VR system depends on the level of presence that a person perceives using the system. (Antonieta Angulo, « Rediscovering Virtual Reality in the Education of Architectural Design: The immersive simulation of spatial experiences », Ambiances [Online], 1 | 2015, Online since 08 September 2015, connection on 21 April 2019. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ambiances/594 ; DOI: 10.4000/ambiances.594) Some rare cases of the application of VR for conceptual and pedagogical purposes do exist: this is the case of the College of Architecture and Planning (CAP) at Ball State University, which has been mobilising VR 2011 tools within its establishment. The simulation laboratory (SimLab) of CAP hosts an installation: the CAP VR Environment. This device allows a single user to move around in environments of unlimited virtual size (real movement is limited to a 6 x 6m room). The user has a VR headset and a tracking system: the user’s position is tracked in physical space, mapped in the three-dimensional model. An architectural experience in VR can be seen as a return to an ‘egocentric’ perception of the individual, involving a series of subjective impressions and emotions – allowing the user of the space to see it as a place in situ and not as an object of external contemplation. The ability to navigate freely through the designed space could be an additional design parameter, in order to verify the sensory perception in real time.

Virtual architecture, pedagogy and co-design

On February 16, 2022, the conference on Virtual Architecture as a pedagogical support for project teaching, through co-design, presented by Julie Milovanovic and Stéphane Safin, will be held. This conference develops in more detail the challenges of collaborative design in VR, applied to an innovative device: the Hyve 3D.

« Teaching in architecture is learning by doing », says Julie Milovanovic, an architect by training and independent researcher. The contribution of teachers in terms of their practical expertise is real, but architecture students lack training in the tools that are so necessary. The question of scale 1 prototypes in architecture schools is rarely raised. They are the subject of options or specific courses. Thus, the two-dimensional plan and section are the tools most often used, allowing the design to be associated with the actual transcription of the building experience.

Following the example of the Coraulis experiment carried out at ENSA Nantes, this singular device opens up the possibility of other ways of designing and representing the project. However, it has yet to be integrated into the teaching of the project at the present time, as it does not yet offer precise content or a ready-made method to its potential users. Indeed, its mastery by a very small handful of teachers and the absence of a method to teach the appropriation by students of this type of device still makes it difficult to integrate it into architecture teaching. This project is indeed the product of research work carried out by CRENAU, ENSA Nantes and CENTRALE Nantes, and allows a 360° immersion (image and spatialized sound). It is intended for researchers, teachers and students, but also for professionals of the city and the territory, and remains open to artistic possibilities (residencies, shows, etc.). « It is particularly well suited to research into the sensitive experience of built environments, techniques for visualizing and analyzing urban projects, co-design and new project pedagogies, links between the arts and sciences, and cultural mediation techniques. » (source : https://aau.archi.fr/contrat-de-recherche/coraulis-centre-dobservation-en-realite-augmentee-et-lieu-dimmersion-sonore/) Other experiments such as HYVE 3D (developed by the Hybrilab in Montreal) are interesting to study on the educational integration of virtual reality tools. It is a device that allows 3D sketching and movement in the virtual space of the model. It encompasses the draughtsman and offers him the possibility of navigating in the model, drawing in 2D on the tablet that he manipulates. This familiar drawing position allows the draughtsman to describe his project in a human scale 1 view with great efficiency. The possibilities of annotating and exchanging information live with the teacher make this equipment particularly relevant when going back and forth from the drawing to the 3D model, from the idea to its consequence in the projected real space. With Hyve, we find the virtual navigation and flexibility of sketching. Sketching is fluid, allowing flexibility in drawing compared to other 3D modelling software. There is no need to enter a measurement to draw, the experience of the paper is as if transcribed to 3D. In the mastery of the tools themselves, we can weave links between high and low tech and what fruitful back and forth can produce as a look at the design. Moreover, it is the project that forms the framework thanks to the device, facilitating communication with the teacher. The principle of the Hyve is reminiscent of a variation of the 360° Panoscope : it is an immersive device comprising a projector (hemispherical lens) positioned above the user. « This project is an initiative of the Society for Arts and Technology [SAT] and is being carried out in the context of a research project funded by Canadian Heritage (Canadian Culture Online) that aims to learn more about the impact of new technologies on cultural practices. » (https://tot.sat.qc.ca/dispositifs_panoscopes.html )

The panoramic anamorphic image is projected inside the surface to match the curved shape of the screen. This greatly simplifies the production and presentation of 360° immersive content, compared to expensive and complex CAVE-type systems and head-mounted displays that do not allow the same space to be shared and viewed in real time from the same point of view. For the Hyve, the vision is inside the tank and not a detached view of the project with the outside looking in to point out alleged errors. It is necessary, within the schools of architecture and design, to value the process of the project, because this is where the learning takes place. At the same time, schools of architecture – with their inherent Beaux Arts heritage – sometimes show a reluctance to use the design method: linked, according to the researcher, to the fear that the creative process will be curtailed. Without a common working basis, the tools are not always well understood by the students. Making the tools available without support is not enough to ensure that the students take up the proposed teaching tools effectively (however innovative they may be). The lecturer then compared the possibilities for collaboration and exchange around the project in a student-teacher discussion: exchange around the classic table, exchange around a scale model, collaboration with a virtual model, etc. The latter allows for a facilitated felt-path that makes it possible to really turn around the corners of the project from several angles. The « felt path » (theorised by Schön, 1981) is the ability to navigate between two types of representation, creating a connection between 2D and 3D, between a human egocentric and an exocentric point of view from above. This is augmented by VR in the relationship to empathy by returning to a user’s point of view. This is a major dimension when design is intended for others. We can ask ourselves as designers: what is architectural quality? Is the qualitative space qualified as perceived by the architect or as perceived by the user? VR is questioned here in what it allows us to perceive according to an egocentric representation, i.e. an internal view.

Then, Stéphane Safin, doctor in ergonomic psychology, took the floor on the more specific topic of co-design of participative interactions and the mechanisms of collaboration mediated by technologies. According to him, the accessibility of co-design to lay users requires a complementarity between scale models and VR. So-called participatory design involves people in the design. But what does the term participation really mean? Stéphane Safin proposes several degrees of analysis of participation: pseudo-design (being informed), user-centred design (being consulted), design thinking (proposing), participative design (deciding), codesign (designing), and finally DIY makers (making).

Giving power to users raises the question of democracy, the emergence of new ideas, and even the customisation of one’s space. The question of copyright is also crucial and continues to be debated: if we make something collectively, who is the moral owner? In codesign, the work on the complementarity between designers and users involves the users at the heart of the creation of ideas – from the beginning of the project in the « creative » phase, then during the preliminary design, and finally the production of the project. The users have the knowledge of use, the designers have the technical knowledge, design methods and representation techniques.The aim is therefore not to learn everything about the designer’s job, but to give users creative methods and representation techniques to work together in co-design. What S. Safin calls « socialVR » allows for a complementarity of representations (between verbal collaboration and bodily engagement).

According to Stojakovic, V and Tepavcevic, B, project pedagogy is also part of the professional world and represents a major communication issue : « The biggest issues, according to Norouzi (2014), in the communication between these two entities is « Habitus Shock », where the client is confused by the process of the building, and the architect often forget on zero experience of the client and his knowledge about that. The education of the client is a fundamental component of the successful client-architect relationship (Siva & London 2011). , p. 3 (Stojakovic, V et Tepavcevic, B (eds.), Towards a new, configurable architecture – Proceedings of the 39th eCAADe Conference – Volume 1, University of Novi Sad, Novi Sad, Serbia, 8-10 September 2021, pp. 403-414)

We can also conjecture new methods and devices applicable to networked platforms in the field of VR. In particular, somatosensory technology refers to the direct interaction of body movements with the devices or the environment around them (without the need for complex, cumbersome or difficult to control control equipment), allowing people to act in an immersive way. At present, the technologies developed – even the lightest ones such as the helmet – present, on the one hand, defects in use (eye fatigue, nausea), and on the other hand, the interactive devices are not light and transparent enough, and the cost is high, which makes it difficult to popularise their content. According to the article Survey on Metaverse: the State-of-the-art, Technologies, Applications, and Challenges, brain-computer interface technologies can be divided into three types at present: invasive (not currently deployed for ethical reasons), semi-invasive and non-invasive. From the futuristic extreme of surgically implanting electrodes into the cerebral cortex, or cranial cavity, to interpreting signals through a handheld device such as a VR headset. (Huansheng Ning,Hang Wang, Yujia Lin, Wenxi Wang, Sahraouik, A Survey on Metaverse: the State-of-the-art, Technologies, Applications, and Challenges, arXiv – CS – Computers and Society, nov. 2021)

STATE OF ART REVIEW

Furthermore, on the occasion of this state of the art completed by the collective experiments conducted, we have been able to identify three registers in the use of metaverse platforms at the present time: entertainment, the creation of flexible environments (which can question architecture in its practice), and the development of virtual twin cities (resulting from strong political will).

The possibilities of these platforms can question several scales of learning for students and professionals:

– Trial and error learning

– Inquiry/problem-based learning

– Game-based learning (roleplay, virtual quests,…)

– Collaborative simulations (learning through the effect of simulating reality or through contact with others, such as learning a language)

– Collaborative constructions (activities related to the construction of virtual environments)

– Design courses or conferences offered in VR (video games, architecture, textile or object design…)

– Experimental virtual laboratory spaces (practical work)

But these digital possibilities also question educational concerns for health on the functioning of the brain and the way in which the understanding of these mechanisms can accompany Alzheimer’s patients or partially paralysed people (in the re-learning of memory paths and the compensation of neuronal structures of the brain). Indeed, in its relearning, the paralysed body reacts as it knew the sensation before the situation of paralysis. It is a question of finding other paths towards a new learning of movement, however everyday it may be, which VR tools make it possible to mobilise through the intention deployed by the brain of the person with a disability. The networking and interpersonal exchanges available in virtual meta universes may constitute an avenue for the medical sector (by mimicry and support towards rehabilitation in the virtual environment). According to Fabrizio de Vico Fallani on the subject of the digital body, « Seeking to understand the functioning of the brain is crucial for identifying the mechanisms of interactions with the external world ». (Source: Fabrizio de Vico Fallani (Inria – Aramis at ICM), Conference, seminar on the Digital Body IN SEARCH OF THE BRAIN? A.C(2).N. 2021-2022 doctoral seminar on BODY AND DIGITAL) He argues that an intention constitutes the imagining of the gesture called « motor imagination », allowing patients to regain the use of a limb in some cases. The need to imagine the gesture before being able to reproduce the movement is a brain mechanism – one that is important to understand in order to deal with cognitive biases within these virtual platforms.

Conducting an experiment on a metaverse: what are the prerequisites?

Several prerequisites for inclusion and mastery of the tools are necessary to ensure optimal use-creation and the development of new skills by design students. The conditions of the educational experiment give the student-subjects the possibility to progressively gain autonomy and to envisage applications of these new VR tools in their future projects. An experiment on the issue of urban comfort is also planned for next April, involving the Coraulis of ENSA Nantes, in collaboration with the school of Recife in Brazil. Considering the mobilisation of a platform (networked web type) in order to interact between students from different countries, may be a way towards a reinforced immersive effect between the subjects of the experiment.

Thus, in general, in order to carry out a given experiment involving a metaverse platform, it is first necessary to define the selection criteria for the platform to be used for the experiment with students, according to the research objectives. The free nature of the platform guarantees inclusiveness in the pedagogical framework, the number of users must allow the whole group subject to the experiment to be able to navigate simultaneously, the modifications of the environment must be flexible and relatively easy to handle in order to avoid discouragement on the part of the subjects, the personalisation of avatars is also a criterion for the projection of the self (whether it is a humanised avatar or a cartoon, the impact of this projection is not to be neglected), and finally, the diversified accessibility of the media must allow a maximum number of devices to be used for the sake of inclusion (telephone, headphones, computer, etc.).

The preparation of the experience underlies the following prerequisites

– a handholding upstream by the persons supervising – the VR tools being sometimes technical to take in hand in their specificities of application to the design, the virtual platforms are very often incomplete or perfectible in this function.

– A need to define objectives oriented to allow students to appropriate the virtual environment – this means making VR equipment available while remaining very present in the first instance to invite students to explore other media than the software with which they are familiar. In a second phase, students gain control and autonomy in their learning by feeding off each other.

– Invite them to hybridize their tools through the physical spatial arrangement – providing large physical surfaces for headset manipulation, and polarized work spaces to allow for hybridization of techniques and tools.

– plan regular group visits to the virtual spaces of peers – this allows them to observe the creative possibilities imagined by others, to confront the technical difficulties encountered and to initiate new approaches.

The use of virtual worlds in education is becoming an alternative innovation to traditional teaching (in project studios, for example, in frontal discussion around a model, sketches, etc.). However, these tools are confronted with several problems such as: the lack of indicators to follow the students’ progress, the lack of defined evaluation parameters, the difficulties to evaluate the collective and individual contributions, the difficulties to maintain the students’ commitment over long periods of time (signs of fatigue, demotivation), the need for a very attentive teacher (requiring a lot of preparation time), and the absence of tutors to guide the learning process of these specific tools. The analysis of student behaviour to improve virtual worlds applied to pedagogy can be envisaged in a personalised and adaptive learning mode – according to the progress of each student. (From the article: Fredy Gavilanes-Sagnay, Edison Loza-Aguirre, Diego Riofrío-Luzcando and Marco Segura-Morales, Improving the use of virtual worlds in education through learning analytics: A state of the art ,Vancouver, Canada, November 2018, DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-02686-8_83.)

Ethics of metavers (environmental impacts, marketing and futuristic image)

However, despite the qualities noted in the experiments conducted so far on case studies, the use of metaverse platforms for educational purposes is not trivial.

According to Google Trends research we can already observe a decline in interest in current metavers. Non-fungible tokens (NFT) as well as the Meta universe offered by the company Facebook seem to slow down with users. In just a few weeks, what was predicted to be the future of the Web has given way to a general scepticism. A recent survey conducted by Klaviyo in the United States concludes that among respondents who know what a metaverse is, 78% believe it is a form of marketing gimmick. Among young people in 2022, 81% of 18-24 year olds consider it to be a trend that is being promoted for advertising purposes; a clear lack of enthusiasm among a population for whom these platforms are intended in their major communication.

The rapid expansion and disinterest of these platforms raises the question of the forms they will take if they are renewed accordingly. The co-design processes that they may engage in seem to be However, it is important to keep in mind the development of tools specialised in the design professions (restitution of physical sensations of interaction in VR, hybrid design methods in the field of design, collective intelligence made possible by the rapid networking of information, immersive use of creation on a scale of 1, fluidity of design, renewal of presentation modes, etc.). The experiments that we can currently carry out are as many resources to identify the criteria of efficiency in their future applications.

We can also try to explain this gradual slowdown in the expansion of these platforms by a global awareness of the ethical aspects of using metavers. The pollution generated by such a technological gamble represents a real energy drain – this is a concern increasingly shared by users. Estimates from 2006 on the very first Meta universe (Second Life) already revealed that the average emission of a single avatar was 1752 kWh/year, equivalent to one inhabitant of Brazil. (source: Survey – Digital Metavers: virtual worlds, real pollution, Enzo Dubesset (Reporterre), March 2022) Moreover, according to calculations by the IT consultancy Green IT, the progressive digitalisation of our society is not innocent in the face of global warming: the sector alone accounts for 4% of the world’s carbon footprint (i.e. « 40% of a European’s sustainable greenhouse gas (GHG) budget »). Free from precise regulation, the virtual spaces of the metaverse are also linked to companies in which the large groups Meta and Microsoft hold shares. For Fabrice Flipo, philosopher of science and technology and teacher-researcher at the Institut Mines-Télécom, « it is essential to quickly introduce a system of market authorisation that would force firms to produce impact studies on the socio-ecological trajectory of their digital projects. (idem) This raises the question of the values that users adhere to and the type of platform they wish to support. Mozilla Hubs, on the other hand, was an open source example that is currently removed from Oculus services. It is also notable that the platforms developed by Meta, for example, benefit from the aura of the Oculus Quest 2, which is considered to be the best VR headset available on the consumer market at the moment. The affluence on this type of platform can therefore be analysed through the prism of a craze for VR devices in general. Thus, the strong economic ideology defended by these platforms suggests that future applications will be geared towards the sale and advertising of goods and services. Many brands such as Adidas, Louis Vuitton or Nike (with the « Nikeland », a metaverse platform derived from the Roblox game) use metavers as places for speculative investment in virtual real estate. « For these companies, it is a laboratory for experimentation with hundreds of millions of people to try out their new concepts at a lower cost and which gives access to an unimaginable quantity of personal data » (Stéphane Bourliataux-Lajoinie, lecturer in digital marketing at the Conservatoire national des arts et métiers in Paris). The first drafts of metaverses are emerging in Fortnite, Roblox, Minecraft or decentralised projects such as The Sandbox or Decentraland. The latter are taking advantage of the users they already have (around 600 million cumulative users) and are trying to take over the virtual space by insisting on communicating on this type of new platform. Some theme parks such as Disneyland also see a market for virtual marketing, wishing to renew their targets through the creation of metaverse platforms with a futuristic image. In this regard, the inventor of Second Life, Philip Rosedale, states: « the business model that Facebook has historically used, based on a very sophisticated type of advertising involving behavioural targeting with a lot of surveillance and personal data, is not a safe model to apply to the metaverse. (source: KEN KOYANAGI, interview for NikkeiAsia, 18 March 2022) The excesses of a platform devoid of precise legislation can certainly drive development towards new innovative possibilities, but they can also lead to forms of violence in virtual space, or to the misappropriation of identities in the absence of firm policies to protect user data (also ensuring the protection of minors).

Metavers thus represent an ambivalent point of vigilance: both rich in the networked design processes they propose (and the lessons we can draw from them towards new applications in the field of design), but also questionable in terms of their ethics and the lack of regulation they are subject to. Furthermore, their factual limitations may raise questions about the inclusiveness they promote, in the case of people with visual or hearing disabilities, or from the point of view of privileged access to virtual reality tools – which are still very expensive.

research report by Marianne-Eva LAVAUR, CRENAU AAU Nantes (accompanied by Laurent LESCOP, Professor, HDR – ENSA Nantes)

31/ 05/ 2022

0 commentaire Laisser un commentaire